MEXICAN FESTIVALS IN THE 16TH - 17TH CENTURIES

Presentation by Pam Price

January 12, 2017

In the presentation today I will discuss how the Spanish tried to make their rule acceptable to Native Americans and other groups in the population.

The Spanish in Mexico gave rise to lively festival traditions. Spanish rulers required their subjects to express their allegiance often and they organized such occasions in festivals on a regular basis. The Spanish in Mexico could not dominate native populations through force alone. From their arrival, they attempted to establish legitimacy through language and ceremony. They believed in the importance of public ritual in convincing their subjects of a moral nature in their rule. Their first aim was authority over persons, not property or trade. It has been said that Spanish colonialism produced the census, while British colonialism produced the map. One focused first on persons, the other on territory. Historians and anthropologists have studied festivals and public ritual throughout the world and this presentation follows in academic approaches which are widely accepted.

In a society in which the rulers and most of the ruled did not speak the same language, it was particularly necessary to produce visual displays of the new, colonial society. Included here were representations of the social and political hierarchies which the colonizers promoted. Also, indigenous people had to be instructed visually in Christian faith and symbolism. Much of the legitimacy of Spanish rule, in the eyes of Spaniards themselves, lay in an evangelical mission.

Colonial officials believed that indigenous people could become accustomed to the colonial regime through rituals of government, passion plays, and Amerindian dances revised to carry Christian-European meanings. The festival traditions which began with Cortés combined Spanish, indigenous, and some African, images and icons. Holiday celebrations offered civic and church leaders the opportunity to organize displays of the virtue which they associated with the colonial regime. In staging processions, plays, and musical performances, the Spanish found willing audiences among native Americans. This I will illustrate with a discussion of the most important annual festival in sixteenth and seventeenth century Mexico City, Corpus Christi, the celebration of the Holy Eucharist. My report is based on an article on this topic which appears in the book, Rituals of Rule, Rituals of Resistance: Public Celebrations and Popular Culture in Mexico, published in 1994 [book cover].

CREATING COLONIAL RULE IN NEW SPAIN: THE ROLE OF FESTIVALS

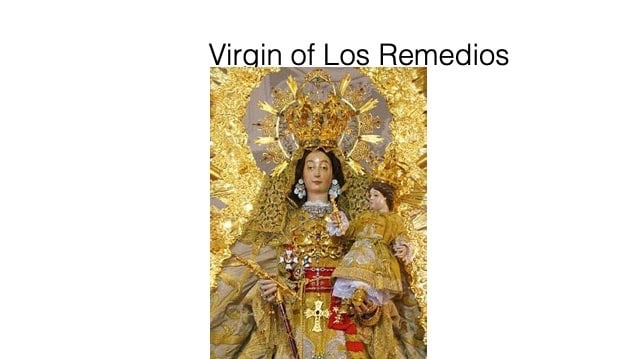

By the early seventeenth century, there were at least ninety festivals a year organized in Mexico City; that’s more than one festival a week. Guilds, religious orders, parishes, convents and lay groups called confraternities celebrated their specific patron saint. The university organized festivities surrounding graduation and the Immaculate Conception of the Virgin Mary. Civic authorities sponsored specific festivals – the entrance of a new viceroy or archbishop, the oath of allegiance to a new monarch, and funeral ceremonies for a deceased king, viceroy, or archbishop. In addition there were the citywide fiestas such as Easter, Carnival, All Saint’s Day, San Hipólito, Corpus Christi, and the festivities dedicated to the Virgin of Los Remedios. San Hipólito day marked the conquest of the Aztec capital by Cortés and the Virgin of Los Remedios was the title of the Virgin Mary associated with the conquistadores and their victories in Mexico [image of virgin from Spain].

Convinced of the importance of the festival, by the late sixteenth century the civic leaders of the city, the cabildo, not the ecclesiastical officials, had assumed the responsibility and the right of sponsoring, organizing, and funding Corpus Christi. They reviewed previous festivals and sought improvement from year to year. Even during times of economic hardship, Corpus as the paramount festival forced officials to engage in tricky financial maneuvers in order to maintain it. Politically speaking, Corpus allowed the government to entertain the populace as a reward for submission, for acceptance of Spanish rule. By providing for the festival and participating in it, the government hoped to make itself admired and obeyed. For the Corpus was different from other celebrations, in that viceregal and municipal officials joined in with the rest of the people, all subservient and humble before the higher moral authority that the Host symbolized. The social hierarchy was articulated by one’s placement in the procession, but with the larger collective submission to the Host, barriers which defined the hierarchy were symbolically weakened. The government’s sponsorship of this festival was to help in legitimizing its rule. We find the importance of Corpus Christi in the response of the government in 1692, one day after the revolt that burned down the viceregal palace – the Corpus Christi procession took place as usual, with the participation of the viceroy.

The Corpus Christi festival, extending over several days, included bull fights, plays, dances, musical performances and religious sermons, but the high point was the procession in which the Eucharist, contained in an elaborate monstrance, was carried out of a side door of the cathedral [image], down streets of Mexico City, and then back into the front of the cathedral. Corpus festivities appear to have taken place as early as 1526 in the viceregal capital, five years after the conquest, and by 1539 they had become a permanent feature of the religious calendar of the city. The celebration grew steadily in size, cost, and sumptuousness, reaching its peak in the late seventeenth and early eighteenth centuries. At this time eight-five groups of lay men, confraternities, participated in a procession that extended about three fourths of a mile – the procession was so long that the end of the line had yet to leave the cathedral even as the beginning returned.

Citizens of the city cleaned the streets, spread sand, and scattered flowers on the path in preparation for the procession. Native Americans constructed a large that canopy that they erected to cover the center of the street. Buildings along the processional route were richly adorned with tapestries and silk or velvet cloth covered with painted images or scenes. For example, in 1697 the silversmiths’ guild decorated its streets with tapestries that depicted the conquest of Mexico. In addition to this decoration some confraternities and guilds built special altars. In 1683 ten such altars were erected. These were generally sumptuous constructions of silver decorated with large votive candles. Mirrors served as backdrops to enhance the Host when it was placed on the altar. Participants lined the steps to the altars with flowers. The procession stopped at each of these altars for the singing of special hymns. The procession also stopped at the entrance to the convent of Santa Clara [convent]. At one point, at the moment the monstrance reached the entrance, the nuns tossed thousands of incense-soaked bits of paper into the crowd in honor of the Host.

The sixteenth and seventeenth centuries were unsettling times for Mexico City. There were periodically food shortages, floods and other natural disasters, epidemics and economic disarray. The city elites were haunted by fear of rebellion. The city was becoming more complex with individuals of mixed Spanish, African, and Native American descent. These were called castas. As early as 1580, the outgoing Viceroy Martin Enríque de Almanza [image] gave instructions to his successor warning of potential instability due to growing numbers of castas. There were significant uprisings in the city, in 1611, 1612, 1624, 1665, 1692, and 1696. Such was the uneasiness in the city that, in 1612, when some escaped pigs ran through the streets late one evening, inhabitants were stricken with panic, believing that mulatto rebels intent on toppling the government had rioted. In the revolt of 1692, a large group of Native Americans and castas stormed the main plaza, forcing the viceroy and Spanish colonists to fear for their lives.

The ruling elite wanted policies that would make city inhabitants doctos – educated persons in the Spanish sense of civilized and European. Festivals were an important method employed. With well-organized festivals the different ethnic groups were to be captivated, entertained, and acculturated by state and church. Festivals were to combat potential dissidence with vivid enactments of the legitimacy of the colonial regime.

The beginnings of this policy are found as early as 1525 at the dedication of the first church in Mexico City. Franciscans friars invited Native Americans from the city and surrounding area to a festival featuring triumphal arches, music, and dancing. It became the practice of the clergy to celebrate religious devotion and reinforce the evangelization process though festivals. For Spaniards otherwise in Mexico festivals also maintained traditions brought from Spain. They demonstrated the grandeur and power of the monarchy, through oaths of allegiance to the king and the spectacular ceremonies organized when a new viceroy entered Mexico City. Festivals provided entertainment. Politically these cultural events were organized and directed toward the potentially disruptive Native Americans and castas that inhabited the city and surrounding area. The aim on the part of the elite was to encourage social and political integration under colonial rule. The most important annual festival toward this end was the celebration of Corpus Christi, Santísimo Sacramento – the Holy Eurcharist.

The Corpus Christi first appeared in the Catholic liturgical calendar during time of Pope Urban IV in 1264, though some kind of Eucharistic devotion existed prior to the thirteenth century. The festival spread throughout Castile and Aragon in the first quarter of the fourteenth century, reaching its peak during the seventeenth century. It was the largest annual festival to take place in Mexico City, the viceregal capital of New Spain, second only, in cost and luxuriousness, to the ceremonies that commemorated the entrance of a new viceroy or the oath of allegiance to a new king. By 1618 the cost of the festival of Corpus amounted to 21 percent of the disposable income of the city fathers. In addition to size and cost, Corpus Christi was unique because all members of society, including all ethnicities, were represented in the festival – as patrons and participants. The festival’s religious significance celebrated the transubstantiation of Christ, but it also was a tribute to Mexico City and its inhabitants. A Spanish visitor to the capital wrote in 1698, “The greatest thing that [Mexico City] can boast about is the frequency of its religious devotion to the Sacraments, its ostentation of so many festivals, and the generosity of spirit of all its inhabitants.” Corpus Christi was the most lavish of these celebrations. Fortunately there is enough documentation of Corpus that we can get a sense of major features of the festival.

Corpus Christi occurred sixty days after Easter, with events taking place it seems over eight days. A high point was a procession of the Blessed Sacrament displayed in a monstrance [image]; this was held after an early morning mass. Different groups were located in the procession according to their status, so placement in the procession reinforced group and ethnic identification. It also reinforced the hierarchical nature of viceregal society. However, participation in the procession symbolized viceregal society as an entity, as a collectivity. The collectivity was celebrated in a festive atmosphere which could have the effect of joining together the city’s different groups, groups which might otherwise be antagonistic. A sense of pride in Mexico City could be a result.

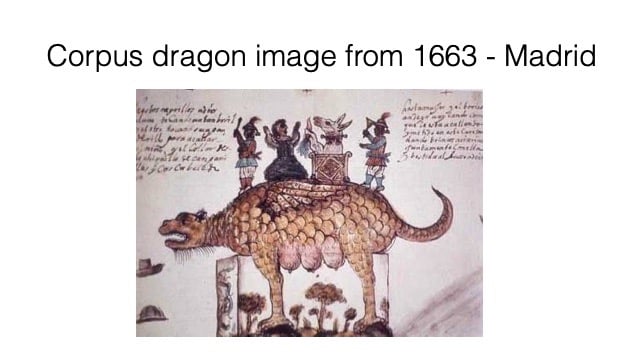

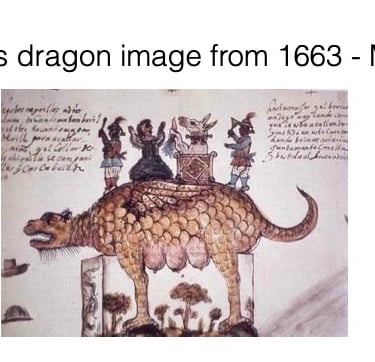

But how was the procession organized? It was led by an assortment of fantasy figures – giants, outsized heads, little devils, and a dragon. The dragon, called a tarasca, came first and symbolized sin conquered by the Holy Spirit. It was made of painted wood and was usually placed on a cart so that it could be wheeled [image from 1663, Madrid]. In seventeenth century Spain the Corpus Christi dragon had seven heads, symbolizing the seven deadly sins. In New Spain the dragon usually had one head. The dragon and the giants were particularly popular, it seems, because it became customary for vendors to sell tarasquitas (little dragons) and gigantitos (little giants) made of paper before and during the procession.

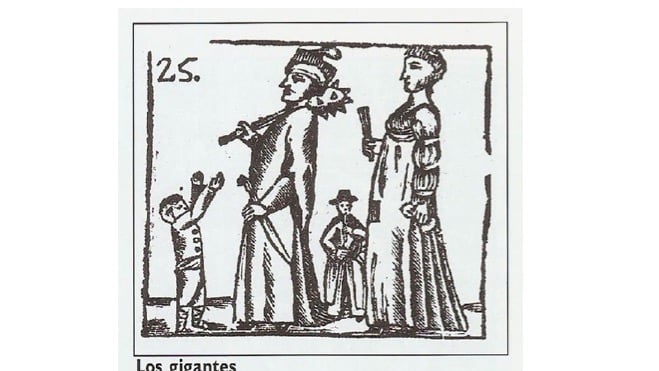

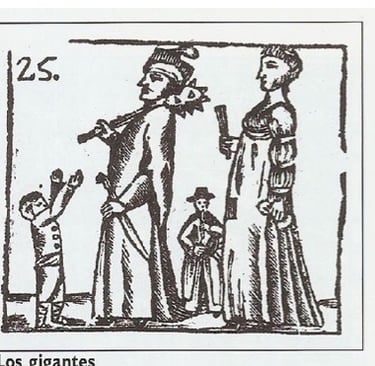

The giants, gigantes[image], were made of wood, paper, metal, fur, wigs, and cloth in the shape of huge individuals, measuring at least five meters in height – more than fifteen feet. They were apparently complicated in design and in many cases made of fine cloth and adorned with silver or gold trim. The giants were brought to life by people inside of them. In Mexico City Africans “walked” the giants and occasionally the civic officials, calbildo, commissioned specially decorated carts or floats to carry them in the procession.

There were, in addition to the giants, cabezudos, or big heads [image, image]. These referred to persons in costume who wore huge heads made of wood and paper. In Spain they traditionally accompanied the giants and chased after small children who taunted them as part of the procession – something like this may also have occurred in the procession in Mexico City. The last fantasy figures were the diablillos or little devils, persons in devil costumes who accompanied the procession. In 1636, for example, the cabildo commissioned ten devil costumes and masks for the procession.

Along with the dragon, giants, devils and big heads at the beginning of the procession came costumed dancers. Three main ethnic groups of the city – Native Americans mulattos, and Spaniards – danced in these processions. Other groups occasionally joined including gypsies, Turks, and Portuguese. Particularly during the sixteenth century the dancers performed on elaborately decorated floats that were stored for reuse the following year. The dances were not limited to the processional route – performances also took place inside the cathedral.

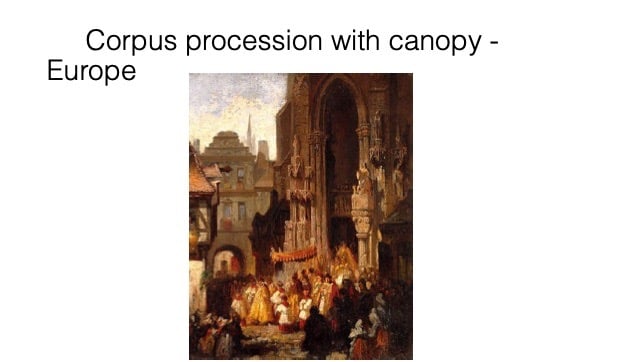

Next in the procession came the guilds, carrying their patron saints adorned with flowers. One witness in 1697 reported that the guilds presented one hundred statues during Corpus. Each guild carried different colored candles as well as their respective banners, and every member wore a tunic and carried a large votive candle in one hand with a bouquet of flowers in the other. The groups of lay persons, confraternities, with their patron saints came next, followed by religious orders, the secular clergy, the Inquisitors, the parishes – each carrying a large cross – and the “angels”, or children from the school of San Juan de Letrán. The children carried candles which illuminated the Eucharist, which followed behind them. The Host could be carried by a prelate – a high-ranking member of the clergy – or it was housed in the monstrance. In any case it was always under a palio, a sumptuous silk canopy trimmed in gold or silver [image]. After the Host marched the viceroy, the members of the audiencia (the High Court), officials, university students and professors, and all other royal officials.

Theatrical performances with a biblical theme were presented as part of the festival on Corpus day. Large bleachers with canopies for shade were constructed for prominent royal, municipal, and ecclesiastical officials so that they might better view the performances. The general public sat on the ground without benefit of shade. On some occasions the Virgin of Remedios attended the performances seated beside the monstrance.

Besides the procession and the plays on Corpus day, various games were organized and there was a fireworks display. The bells of Mexico City’s many churches were rung in synchronization.

The importance which the imperial government attributed to Corpus Christi is seen in support which viceroys periodically gave the festival. They directly aided and enhanced the celebration, contributing to its rise as the premier festival in the city. They intervened directly to increase its sumptuousness and popular participation. Two viceroys stand out for their contributions – Luis de Valasco, the Marquis of Salinas, and Gaspar de Zúñiga y Acevedo, the Count of Monterrey. Viceroy Velasco, between 1590 and 1595 [image], specifically added the theatrical performance presented on the final day of Corpus and the dance of the Spaniards. Before this time it appears that Native American dance groups made up the majority of musical and dance performances. With regard to the indigenous population he ordered that Indians from nearby villages play their harps and dance each day of the Corpus. He was particularly keen that Indian musicians, even those living at some distance from the capital, be recruited to play in the city during the festival. This practice continued into the seventeenth century. In addition the viceroy ordered that all guilds were to build fantasy figures – giants, monsters, masked and costumed persons – for the procession. This decree seemed difficult to accomplish because as early as 1585 the guilds petitioned the high court to escape some of the expenditures of Corpus. The second viceroy I mentioned, was the Count of Monterrey [image] – 1595-1603. He ordered the city officials, to make Corpus Christi the premier festival of the city. He demanded improved dramatic performances, costumes, and better-dressed giants and big heads. Native American performers were instructed to improve their dances, and more indigenous musicians were hired. In addition the viceroy added mock jousts and three days of bullfights. He settled disputes between city fathers and troupe directors regarding cost and drama selection. The Count of Monterrey appears to have been the first viceroy to donate money specifically for Corpus. The city government had spent all of its funds on the funeral ceremonies of Philip II in 1599. Three years later he lent the council money, again specifically for the festival. In fact, there was an economic decline in city revenues in the early seventeenth century and only the willingness of several viceroys permitted Corpus to survive and grow.

The importance of Corpus to viceroys is seen not only in their continued financial and moral support, but also by their efforts to change certain Corpus traditions even if it created a scandal. Questions of honor and protocol caused concern at the viceregal court, and in the city generally. At issue regarding Corrpus was the question of how close to the Eucharist one was placed in the procession. Proximity to the monstrance, the recognized place of prestige, was a continuous point of contention among the guilds and confraternities, and royal officials also took part in the rivalry. In the mid seventeenth century, the viceroy – Count of Alba de Liste [image] – created a major public disturbance by stopping the procession mid-march in order to implement his will. In 1651 he demanded that his pages replace church officials in the processional line. Traditionally, the ecclesiastical leaders followed directly behind the monstrance, thereby serving as the entourage for the Host. Perhaps the viceroy wanted to further cement, in the minds of the public, the relationship between the Eucharist and the ruling authorities. The Eucharist represented higher moral authority and placing royal servants closer to the monstrance was strengthening the civilians at the expense of the clergy. Scandal was the result – the viceroy abandoned the procession in midstride and ordered the guilds and confraternities to stop where they were. He placed the monstrance, which had not yet left the cathedral, under guard. When the clergy attempted to resume the procession in violation of viceregal orders, a small brawl broke out in which the monstrance was almost knocked over and the clergy abandoned the procession. The crowd then turned unruly. Informed of the commotion at the cathedral, the viceroy ordered the procession to continue without any of the city’s clergy. The ecclesiastical members directly involved did not take this attempt to alter the procession lying down. They immediately fired off a series of protests to Spain.

The clergy’s petitions to the king emphasized the position of the church regarding the religious celebration. Their arguments relied on both the religious nature and tradition of the festival. The viceroy, the Count of Alba de Liste, for his part, claimed his role as the supreme authority of New Spain – he claimed viceregal prerogative as the stand-in for the king in the colony. The Spanish court responded by reinforcing the viceroy’s position. A symbolic relationship between the Host and the civil and royal authority was emphasized at the expense of the ecclesiastical leaders.

When we examine the cabildo, the city fathers, we get an even better illustration of the Corpus Christi to the civil authorities in Mexico City. City officials were directly responsible for the success or failure of Corpus as an agent of political integration under colonial rule. The cabildo actively promoted and regulated the festival from as early as 1529, eight years after the conquest. City officials held the canopy above the Eucharist in the procession – this was a privilege they struggled to maintain against members of the audiencia, the High Court. The dispute revolved around whether the cabildo or the audiencia had the authority to choose individuals who would carry the poles that held up the canopy over the monstrance in the great procession. The issue first surfaced in 1533 when the municipal authorities refused to walk in the procession until the king of Spain, no less, ruled on the matter. Over time the canopy was expanded in size in order to accommodate more dignitaries. Originally there were only twelve canopy poles, but by 1675 there were fifty. The cabildo manage to secure their place by enlarging the canopy with more supporting poles.

The cabildo defined its relationship to Corpus by a sense of duty, a special obligation to provide entertainment. In 1617, speaking of festivals in general, a high-ranking official said that celebrations were important for making the public happy. He added that neglecting them put the “public in a bad mood” and “left their spirits forlorn”. The cabildo believed that festivals in general helped maintain order and stability, but they formed a special bond with Corpus Christi. Councilmen linked the identity of the city to the ostentation, the innovation, the grandeur of Corpus. The city’s identification with Corpus is illustrated by its continued financial support of the festival, in some cases at the expense of a sound budget. The seventeenth century brought financial weakness to the city and the cabildo struggled to provide necessary services. Through borrowing and other budgetary measures the city maintained the seventeenth-century Corpus Christi at a level of sumptuousness roughly equal to that of the late sixteenth century. The essential ingredients of the festival remained through the seventeenth century. In the review of the accounts of 1618 the councilmen listed what they believed were the most important elements of Corpus – theatrical performances, dances, fireworks, giants and other creations, candles, and patronage of the children of San Juan de Letrán who marched in the procession. By mid-seventeenth century the economy and, consequently, the city budget improved. By the end of the seventeenth century and the beginning of the eighteenth centuries Corpus reached another peak in sumptuousness. Corpus Christi and other festivals were, however, about to undergo a series of major changes.

In 1700 a grandson of the French Louis XIV acceded to the Spanish throne, the last Hapsburg king having died childless. Ties with France were strengthened under the Spanish Bourbons and enlightenment ideas of rationality and civilized behavior held stronger sway. In this context, the elements of the Corpus Christi festival in Mexico City came under new scrutiny.

In an effort to maximize efficiency and the benefits of an overseas empire, generally, the Bourbon bureaucracy instituted a series of administrative, military, economic and social reforms. With regard to social reforms Bourbon officials sought to instill the populace with what they perceived to be modern behavior. This included an attack on certain excesses that they considered vulgar, unseemly, improper, and decadent. Festivals, with their mixture of the sacred and the profane, were in the line of Bourbon fire. Festivals should be solemn affairs that should proceed in an orderly and respectful manner, serving as a model of good behavior and reverence. One Spanish writer observed about good government and festivals, “the first object ought to be to watch over the Indians in order to make them rational, civilized…. Whatever they earn by working, they spend on festivals and large dinners and drunken binges with which they celebrate these festivals, that really should be called bacchanalias rather than civilized and religious [celebrations]”. About Corpus he added: “Nothing dishonors and stains these events as the permissiveness and tolerance, in the name of confraternities, that allows [the participation of] a crowd of drunk, miserable naked Indians wearing costumes”.

The revolt of 1692 was a powerful memory, this was when the viceregal palace was set on fire during the period of the Corpus festival. Thus, the colonial elite and the authorities had begun to view popular traditions of Mexico City as customs containing seeds of subversion, which had to be eliminated.

Festivals, particularly Corpus Christi, brought many villagers from miles away to the capital. So many people, so much alcohol flowing, and so much holiday behavior, it was believed, created too volatile an atmosphere, increasing the possibility of disorder and revolt. The revolt of 1692 had been sparked by a food shortage and reports of grain hoarding, but it had taken place during the celebration of Corpus. The rioters, however, eventually abandoned their uprising because of their devotion to the Holy Eucharist. Apparently, two Franciscan friars carried the Host into the furious crowd and begged the Native Americans and castas to put out the fire at the viceregal palace and go home, all in the name of Santísimo Sacramento. In 1701 fear of a revolt once again permeated the procession. Bourbon officials had come to view the festival not as a symbolic means to maintain order but rather as an occasion that could shatter stability. Festivals required reform, they concluded, to strengthen elite control of festive spaces. The reform process took time and was widely applied throughout the festival calendar. With regard to Corpus, reform efforts began with dances, requiring authorization and approval from the cabildo and ecclesiastical authorities. By 1744 the cabildo had stopped contracting dancers altogether. Regulations outlawed food stalls and vendors from the processional route and rigorously banned drinking from the festival. In 1777 municipal expenditures for Corpus were drastically cut back. The final reform of Corpus occurred in 1790 when the viceroy, the Count of Revillagigedo [image] issued a decree permanently banning the dragon, the giants, and the big heads.

In the nineteenth century, even after independence from Spain, the religious celebration dedicated to the Holy Eucharist inside the cathedral continued, but the large procession and other outdoor activities such as the plays were gone. After the Mexican revolution in 1920 the Corpus celebration regained some of its former splendor. And by the end of the 20th century folkloric Native American dance performances once again accompanied the festival and vendors were selling miniature paper constructions of animals to children.

We may ask why the reform of Corpus continued even after independence from Spain, until 1920 – it could be because the city elites had become convinced of the potential for revolt which lay in bringing masses of people together for an eight day fiesta with lively profane elements. But we can see the popular festival traditions in Mexico City as contributing to the emergence of Mexican national identity, which of course found expression in the independence movement. We see Mexican identity expressed today in the colorful processions – the parades – on the streets of towns and cities.

Taken from “Giants and Gypsies: Corpus Christi in Colonial Mexico City,” by Linda A Curcio-Nagy, in Rituals of Rule, Rituals of Resistance: Public Celebrations and Popular Culture in Mexico (Wilmington, DE: Scholarly Resources Inc., 1994), 1-26. I use wording by Curcio-Nagy without attribution in piece and recommend reading this very interesting article. - Pam Price